- Category:

- News

Maximising the benefits of e-scooters in UK cities

Local authorities in the UK must take an active role in e-scooter deployment and learn from previous cases across Europe to maximise the benefits and ensure a smooth integration with today’s transport network, writes David Philipson for Transport as a Service magazine. His report, Maximising the benefits of e-scooter deployment in cities, is available now for free.

You’ll have seen cycle lanes popping up across town and city centres in the UK since the start of the coronavirus lockdown, erected to aid social distancing and enable journeys without the need for public transport where the risk of cross-contamination is greater.

This move from local authorities shows the rising demand for micro-mobility – short-distance transport options like bikes and scooters, sometimes with electric motors – which are becoming a more practical proposition for a broader range of people.

As a result, and in light of the coronavirus outbreak, the UK Government brought forward trials of electric powered scooters (e-scooters) to give the public, primarily key workers, an alternative form of low carbon transportation to aid a green recovery.

Pioneered in 2018 by Lime and Bird in the United States, e-scooters are intended as a sustainable method of ‘first and last mile’ transportation and have grown in popularity ever since, particularly with commuters between bus or train stations and places of work or university, or lone travellers making short journeys where a car or taxi has previously been the preferred option.

The UK trials are limited to rental e-scooters, rather than private ownership, and in specific towns and cities with temporary laws enacted to allow deployment and allow users to ride them legally.

Riders must be over the age of 16 with a valid driver’s licence while the e-scooters are limited to 55 kg, 25 kph (15.5 mph), and roads and cycle lanes – helmets are recommended but are not a legal requirement.

Rental e-scooters are predominantly dockless which offers users the convenience and freedom to start and end their journeys at any location (within a zone restricted by GPS) without parking fees; typically, devices with low charge are collected, recharged and redeployed to hotspots overnight.

Historically, regulation came after deployment, causing social and transport problems, however the UK trials, expected to last up to one year, give local authorities the opportunity to assess the impacts and use the results to influence future laws.

As communities adjust to new and disruptive transport methods, those impacts should be evaluated in light of the benefits to society and the environment.

Taking people out of cars reduces congestion which improves journey times and benefits local air quality, therefore policy should promote e-scooters as an alternative to cars rather than public transport or active travel (walking and cycling).

Data from various e-scooter studies shows that around 30% of e-scooter journeys replace car travel (a combination of private car use and ride-hail e.g. taxi, Uber or Lyft), 50% of rides replace active travel, 12.5% of rides replace public transport and 7.5% of users would not have made the trip if e-scooters were not available.

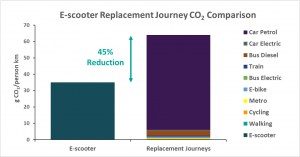

Using those figures for modal shift, Cenex has calculated that e-scooters reduce CO2 emissions by 45% across all journeys.

Figure 1: Calculated CO2 impact across all e-scooter journeys

Car journeys have the largest carbon footprint, therefore the higher the percentage of car travel replaced by e-scooter journeys, the greater the environmental benefit, whereas e-scooter rides that replace active travel increase the carbon footprint of the transport network.

The downside to rental e-scooters is the necessity to recharge, which can also have a negative environmental impact.

By the end of each day, e-scooters can be dispersed across a large area, creating inefficient and long travel patterns for collection vehicles (typically with internal combustion engines) which must be accounted for in the total emissions output.

Data from Voi Technology shows that this has improved over time, with life-cycle CO2 reducing by 70% since January 2019 – from 120 g CO2 equivalent per km to 35 g in March 2020 – by switching to renewable electricity for charging, using an electric cargo bike to replace batteries in situ, and incentivising rider behaviour to improve efficiency.

Continued emission savings are vital as the UK targets net zero by 2050 and any small improvements are positive steps towards achieving this.

Replacing car journeys with e-scooters also benefits other road users, as congestion eases and journey times improve.

Global vehicle numbers currently grow by around 80 million vehicles per year, causing significant increases in the travel time for drivers in slow, stop-start traffic, especially during peak travel times during the morning and afternoon.

In the UK, 58% of car journeys are less than 5 miles (in urban environments 69% of car journeys are less than 3 miles) while congestion causes an average of 178 lost hours per year in the UK and an associated cost of £8 billion.

Their compact nature and operability make e-scooters ideal for short journeys in urban environments – popping into town for lunch, short commutes to work or getting around university campus – and can be quicker than driving through city traffic, especially with dockless parking.

The price points of e-scooters open them to citizens from a broader range of socioeconomic status, as rentals have no capital outlay and can cost as little as £2 for a short trip – a similar cost to parking a car.

As e-scooters become more widely adopted, congestion should begin to ease in city centres decreasing journey times for private cars, however, city planners may look to reallocate road space from cars to e-scooter, bikes and walking, demonstrated by the ‘pop-up lanes’ in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic.

To support the growing popularity of e-scooters in the city centre, local authorities in Sofia, Bulgaria’s capital, established specific regulation and policies for operators and users before widespread deployment.

This included reallocating 160 car parking spaces for micro-mobility parking, and establishing speed and age limits, and conditions for compulsory helmets and reflective clothing.

Potential operators were required to share captured data with the city in order to receive a license to operate within the city, thereby controlling vehicle numbers and ensuring appropriate parking provision that has little effect on pedestrian footpaths.

In contrast, Paris, France, saw rapid growth – 20,000 vehicles deployed by 12 operators within 12 months – with little regulation; abandoned e-scooters littering the streets, and the number of accidents with pedestrians and other road users, caused major concern.

As a result, mandatory fines and fees were introduced for operators and users, 2,500 parking spaces were dedicated to e-scooters, and, to ensure long term sustainability, operators are now selected following a tender based on user safety, operations, and environmental responsibility.

Each regulatory decision should be taken at a local level based on influencing factors rather than blanket across all e-scooters: Barcelona, Spain, allows e-scooters in cycle lanes at speeds up to 10 kph and up to 30 kph on the roads, but cannot be used on pavements, whereas Berlin, Germany, has a blanket speed of 20 kph for cycle lanes and roads, but also restricts their use on pavements.

As each deployment area is different, there are key considerations for local authorities to ensure the benefits are maximised and the negatives minimised.

The examples of Sofia and Paris highlight the importance of cooperation between private operators and local authorities to ensure sustainability.

Public transport and active travel should be the backbone of sustainable urban mobility, and shared micro-mobility services need to support these modes rather than compete against them – it is the role of local authorities to communicate this to operators and dictate where e-scooters are best placed to ensure they contribute to the city’s sustainability objectives, and not just for the operators’ business case.

Sharing local knowledge of key deployment sites – including train stations, bus stations, mobility hubs, retail hubs, technology industrial parks and universities, parks, and places of significant interest – will benefit the operator’s business case with high utilisation and fill gaps in the transport network so that a high proportion of e-scooter journeys replace car journeys (and reduce emissions and congestion).

Infrastructure is also a key consideration, allocating road space for cars, bikes and scooters, and parking space and docking stations to smoothly integrate e-scooters into the transport network and minimise disruption.

Transport planners have historically allocated a large proportion of public space to privately owned vehicles and reallocating this space – road lanes, parking spaces – for sustainable modes of transport removes the dependency on cars and opens opportunities, and possibly demand, for low emission alternatives such as bikes and e-scooters.

Local authorities and e-scooter operators should also collaborate on the large amounts of user and operational data available to analyse transport systems and understand usage patterns – when and where traffic is more intense, and parking has more peaks – to identify priority areas for future improvements and ensure sustainability.

As the results of the UK trials come to light, the impacts evaluated, and policy established, e-scooters will transition from a disruptive technology to socially and environmentally beneficial, but only if lessons are learnt from previous deployment across Europe, and local authorities take an active role early on.

Through collaboration, planning and regulation, e-scooters represent a large piece of the puzzle in decarbonising urban transport, and looking at other e-scooter deployment cases can help prepare cities for future transport innovations.

David Philipson, Transport Technical Specialist at Cenex, said:

“E-scooters have their place in the transport networks of the present and future, offering first and last mile travel solutions that are inclusive and sustainable.

“However, without appropriate implementation, management, and regulation they can disrupt the transport network, and the city as a whole, in a negative way.

“It is evident that e-scooters are here to stay, with operators committed to continual improvements for the benefit of both the environment and society.

“Though still in its infancy as an industry, e-scooters are already providing a genuine, affordable, green solution to private car use in city centres which will only improve over time.

“Local authorities need to take an active role in the deployment of e-scooters in their regions, setting out regulations for operators in order to ensure that e-scooters meet both their ambitions and their citizens’ needs.”

Cenex lowers your emissions through innovation in transport and energy infrastructure, operating as an independent, not for profit, consultancy and research technology organisation.